Buena Vista Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians of California is a federally recognized Indian tribe. The Tribe has been listed by the Secretary of the Interior as such since 1985. The Tribe’s Rancheria land is a 67-acre parcel in Amador County just outside the town of Buena Vista.

The Me-Wuk Indians of the Buena Vista Rancheria are an integral part of California’s Native American history. They lived in and around what is now Amador County for thousands of years.

The Oliver family has roots in Amador County as early as 1817

As a result of the Mission Period, Gold Rush and then diseases that Indian people had never been exposed to, the Me-Wuks’ numbers shrunk dramatically over the last three centuries.

By the late 19th Century, the Me-Wuks in the Amador County area were reduced to a smattering of individual families. The Buena Vista Band and its descendents lived through some of the most horrific times in American history…from Casus Oliver and his mother escaping Mission San Jose, to continuing to practice their culture when it was forbidden. Casus Oliver came to Amador County with his mother and joined the settlement of Upusani.

In the early 20th Century, the federal government had created a network of small “Rancherias” for landless Indian tribes in California, mostly in the northern part of the state. The United States purchased the Buena Vista Rancheria in 1927 with money appropriated by the Acts of June 21, 1906 (34 Stat. 325-328) and April 30, 1908. (35 Stat. 70-76).

Today is what became of one such family, direct lineeal descendents of Louis and Annie Oliver.

The story of Casus Oliver begins in the early 1800s. Casus and his mother were among the hundreds of Yokuts and Me-Wuk people of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys who were taken to Mission San Jose between 1811 and 1836, and their story is a welcome reminder that the Spanish missions did not succeed in destroying the native culture. Casus’s mother brought him to Upusani Village, now Buena Vista, in the early 1880s.

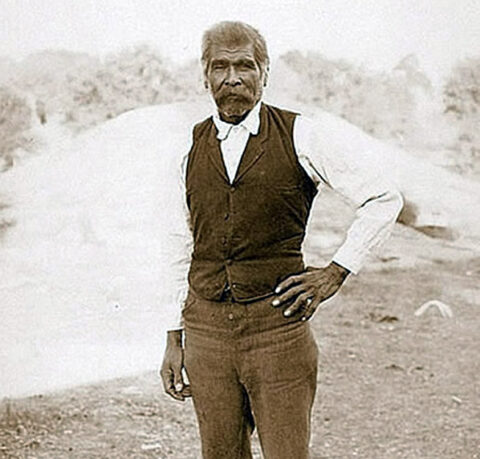

In 1903, C. Hart Merriam interviewed Casus Oliver at Upusani and noted:

“His mother was stolen by the Spaniards when young and taken to the mission at San Jose, where the old man (Casus Oliver) spent his early boyhood. His mother took him and escaped. She joined a village of Mokalumne (Mokelumne) Indians near where the town of Lockeford now stands, and there they lived many many years – by far the greater part of his life – until the white men took up all the land and the remaining Mokalumnes were driven away and scattered. Now the tribe is practically extinct. This happened about twenty years ago as near as the old man can remember. He then came up to Amador County and joined the Mu-wa (Me-Wuk) settlement of You-poo-san-ne (Upusani), where he has since made his home. “

– Deeper than gold: A guide to Indian life in the Sierra foothills, by Brian Bibby, Dugan Aguilar, 2005

It was there Casus met his wife, Lizzie Ganor, daughter of Susie and Charlie Ganor and documents tell of the Ganor family living at Buena Vista since “the sun first came up.”

Sometime before the turn of the century, Casus Oliver became the Headman at Upusani. Casus and Lizzie Oliver began their family at Upusani in the late 1800’s, and had four children, John, Louie, Joseph and Josephine. Lizzie died in 1899, and years later, Casus remarried Amanda Winn, who had 12 children from previous marriages.

Casus settled in Buena Vista with his family, and remained Headman of Upusani until his death in 1916. Casus and Lizzie’s children remained on the reservation for awhile, but Joseph died at an early age, and John and Josephine moved out of Amador County some time before the Indian Application for Enrollment requirements of 1929. John moved to Sonoma where he died in 1940. Josephine moved to Auburn and died in 1960.

Only Louie remained, with his wife, Annie, and their three children. At that time, members of Indian Rancherias filed records of enrollment with the county of jurisdiction, and the documents were completed by representatives of the government. Because most Native Americans spoke little or no English, translation was often based on the phonetic sounds, such as Cano for Ganor; and Alaba for Oliver . These ‘sound-like’ names are found in various records when referring to the Oliver or Ganor family. 1910 Census doc

Louie Oliver was 27 years old at the time of his father, Casus’ death in 1916. He and his wife, Annie, had one daughter at that time. They lived at the Buena Vista Rancheria and eventually had five children; Myrtle, Lucille, Elinor, Enos and Marie.

In 1927, the federal government purchased the Buena Vista property from Louie and Marjory Alpers in fee for the use of homeless Indians. The Olivers lived on the property at the time.

When the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, Louie and Annie Oliver remained on the property. Myrtle and Marie died as children and according to the United States Indian Census Roll in 1941, Louie and Annie Oliver and their three children, Lucille, Elinor and Enos were the only ‘enrolled’ occupants of the Buena Vista Rancheria.

And when Congress passed the California Rancheria Act in 1958, Louie and Annie Oliver were deeded the property:

“Mr. Oliver is the only assignee and he and his family are the only Indians who have lived on the Rancheria since 1935.”

Louie and Annie loved their heritage and their land. They celebrated their customs and their culture through annual gatherings, welcoming all tribes.

“Sponsoring a “feed” was a traditional responsibility for a Me-Wwuk captain, and one that Casus’s son Louie maintained following his father’s death in 1916. Several long tables were set out and groups of people would take turns eating. Elders remember Louie pacing back and forth behind seated diners, repeatedly encouraging them to eat heartily by bellowing, “ewway’epo! ewway’epo!” These annual gatherings took place on Memorial Day and lasted into the late 1960’s. Louie Oliver died in 1973. Today, though the roundhouse has long since collapsed and reverted to the earth, and the old hosts have passed on, memories of sunny May afternoons, abundant servings of good food, and warm hospitality remain in the hearts and minds of many.”

– Deeper Than Gold: A guide to Indian life in the Sierra foothills, by Brian Bibby, Dugan Aguilar, 2005

Over the years, it was difficult for tribes, and the promised assistance from the federal governments never came. Not until 1983 did the Buena Vista and 16 other tribes win their law suit to be reinstated as federally-recognized Indian tribes, and reestablish their rights to critical forms of federal assistance. .

But Louie and Annie remained on the land they knew as their home. If not for them, the Buena Vista Rancheria would not exist, for had they moved on as did their siblings, the land would not have remained in the family. Even after their children moved on, Louie and Annie stayed on the reservation.

Their middle child, Elinor, gave them a grandchild, Jesse Flying Cloud Pope.

Jesse was only 7 when his mother, Elinor, died in 1951, and Jesse spent most of his youth on the Rancheria with his grandfather, Louie.

Jesse and Barbara Hatfield had one child, Rhonda L. Morningstar Pope. Like her father, Rhonda lost her parent at a young age, leaving her without a father at the age of 5.

The Oliver family history is one of tradition, culture, dedication and courage. Today, the Buena Vista Rancheria remains the home to the Oliver descendents, and is alive with the traditions and culture that Louie and Annie brought to their beloved reservation.